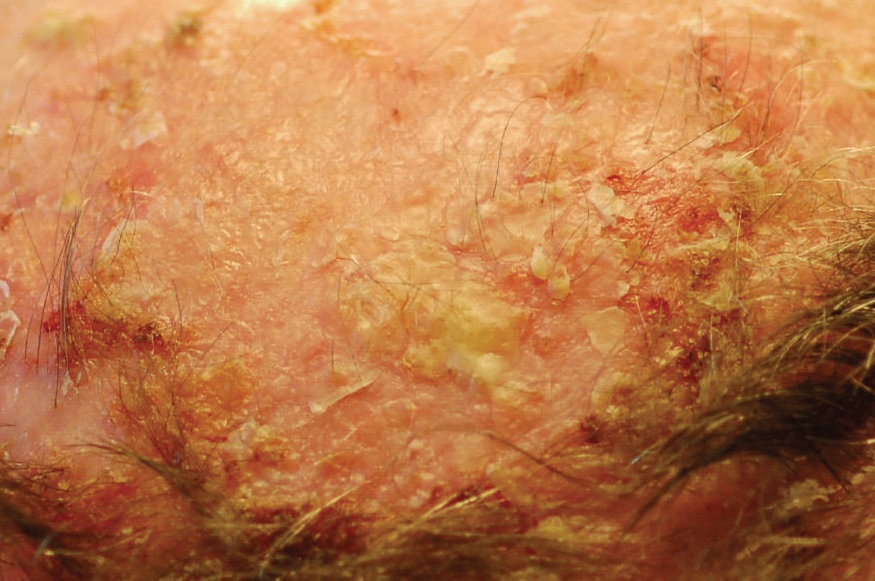

Image: "Multiple lesions of actinic keratosis on the scalp of a 55-year-old man" by C.Morice, A. Acher, N. Soufir, M. Michel, F. Comoz, D. Leroy, and L. Verneuil is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Link to the source. Source: "Multifocal Aggressive Squamous Cell Carcinomas Induced by Prolonged Voriconazole Therapy: A Case Report", Case Reports in Medicine 2010.

Actinic Keratosis

Introduction | Aetiology and Risk Factors | Clinical Presentation | Diagnosis | Management and Treatment | Prevention | When to Refer | References

Introduction

Actinic keratosis, also known as solar keratosis, is a common skin condition characterised by rough, scaly patches that develop on sun-exposed areas of the skin. It is caused by long-term exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun or tanning beds. Actinic keratosis is considered a precancerous lesion because it can progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) if left untreated. Early detection and management are crucial to prevent progression to skin cancer.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

Actinic keratosis is primarily caused by cumulative UV radiation exposure, which leads to DNA damage in skin cells. Key risk factors include:

- Chronic Sun Exposure: Individuals who spend a lot of time outdoors, such as those with outdoor occupations or hobbies, are at increased risk.

- Skin Type: People with fair skin, light hair, and light eyes are more susceptible to UV damage and, consequently, actinic keratosis.

- Age: The risk increases with age due to the cumulative effects of sun exposure over time.

- Geographic Location: Living in areas with high UV radiation levels, such as near the equator or at high altitudes, increases the risk.

- Immunosuppression: Individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those on immunosuppressive drugs or with conditions like HIV, are at higher risk.

- History of Sunburns: A history of frequent or severe sunburns, especially in childhood, increases the risk of developing actinic keratosis later in life.

Clinical Presentation

Actinic keratosis typically presents with the following features:

- Rough, Scaly Patches: The hallmark of actinic keratosis is a rough, sandpaper-like texture on the skin. The lesions are often easier to feel than to see.

- Red or Brown Lesions: The patches may appear red, pink, brown, or skin-coloured, and they often have a scaly or crusty surface.

- Flat or Slightly Raised: Lesions can be flat or slightly elevated, and they may range in size from a few millimetres to a centimetre or more.

- Location: Commonly affected areas include the face, ears, scalp, neck, forearms, and backs of the hands—areas frequently exposed to the sun.

- Tenderness or Itching: Lesions may be tender to the touch or cause itching, but they are usually asymptomatic.

- Multiple Lesions: Actinic keratosis often occurs in clusters, and the presence of multiple lesions increases the risk of progression to SCC.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of actinic keratosis is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic appearance and history of sun exposure:

- History: Take a detailed history, including the patient’s sun exposure habits, history of sunburns, and any previous skin cancers or precancerous lesions.

- Physical Examination: Examine the skin for rough, scaly patches, particularly on sun-exposed areas. Use palpation to feel for the characteristic rough texture of the lesions.

- Dermatoscopy: Dermatoscopy can aid in the diagnosis by revealing features such as a scaly surface, erythema, and the absence of a pigment network, which are typical of actinic keratosis.

- Skin Biopsy: If there is uncertainty about the diagnosis or concern for progression to SCC, a skin biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis and assess the degree of atypia.

Management and Treatment

Management of actinic keratosis aims to remove or reduce lesions and prevent progression to squamous cell carcinoma:

1. Topical Treatments

- 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) Cream: A topical chemotherapy agent that destroys actinic keratosis cells by inhibiting DNA synthesis. It is applied once or twice daily for several weeks, causing inflammation and crusting before healing.

2. Procedural Treatments

- Cryotherapy: The most common treatment for actinic keratosis, cryotherapy involves freezing the lesion with liquid nitrogen, causing the abnormal cells to slough off. It is quick and effective, with minimal downtime.

- Curettage and Electrocautery: This involves scraping off the lesion with a curette and then using heat to destroy any remaining abnormal cells. It is useful for thicker or more resistant lesions.

- Photodynamic Therapy (PDT): PDT involves applying a photosensitising agent to the lesions, followed by exposure to a specific wavelength of light. This causes selective destruction of abnormal cells. It is effective for widespread actinic keratosis.

- Laser Therapy: Lasers can be used to remove actinic keratosis by vaporising the affected tissue. It is often used for cosmetic reasons or in cases where other treatments have failed.

3. Lifestyle and Supportive Care

- Sun Protection: Advise patients to use broad-spectrum sunscreen with SPF 30 or higher, wear protective clothing, and seek shade, especially during peak UV hours.

- Avoid Tanning Beds: Strongly discourage the use of tanning beds, which significantly increase the risk of actinic keratosis and skin cancer.

- Regular Skin Examinations: Encourage patients to perform regular self-examinations and to see a healthcare provider for routine skin checks, particularly if they have a history of actinic keratosis or skin cancer.

- Vitamin D Intake: Patients who avoid sun exposure should ensure adequate vitamin D intake through diet or supplements, as recommended by their healthcare provider.

When to Refer

Referral to a dermatologist may be necessary in the following situations:

- Uncertain Diagnosis: If there is doubt about the diagnosis or concern for malignancy, such as SCC, referral for further evaluation is advised.

- Extensive or Refractory Lesions: Patients with widespread or resistant actinic keratosis may require specialised treatments such as photodynamic therapy or laser therapy.

- Cosmetic Concerns: Patients seeking cosmetic improvement or those with actinic keratosis in cosmetically sensitive areas may benefit from referral for specialised procedures.

References

- British Association of Dermatologists (2024) Guidelines for the Management of Actinic Keratosis. Available at: https://www.bad.org.uk (Accessed: 26 August 2024).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2024) Actinic Keratosis: Diagnosis and Management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng103 (Accessed: 26 August 2024).

- British National Formulary (2024) Topical and Procedural Treatments for Dermatological Conditions. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/ (Accessed: 26 August 2024).

Check out our YouTube channel

Blueprint Page

Explore the comprehensive blueprint for Physician Associates, covering all essential topics and resources.

Book Your Session

Enhance your skills with personalised tutoring sessions tailored for Physician Associates.